How to Actually Develop 'Good Taste'

Understanding what moves you vs. when you're being moved for the wrong reasons.

Good afternoon. Last week, I had the pleasure of moderating a panel with two astronauts, General Charlie Duke and Nicole Stott, at CD Peacock for Omega. Duke was part of the Apollo program and was the pilot of the Lunar Module on Apollo 16, when he became the 10th person to walk on the moon. He also served as CAPCOM for Apollo 11 when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the moon. Duke’s from North Carolina and lives in Texas now—his Southern drawl charmed Americans listening to that first moon landing, and I’m happy to say that at age 90, he’s still just as charming. Here’s me with Charlie and Nicole:

General Duke was fittingly wearing his Omega Speedmaster Apollo 16. Funny enough, he says he somehow ended up with two, so gave one to his son.

In today’s email: How to actually develop good taste, and trying to find an antidote to always wanting “more”:

Paid subscribers get 2 emails/week, 10% off in the Unpolished Store, and a $50 discount to Watchcheck. Upgrade now for $99/year:

The Roundup

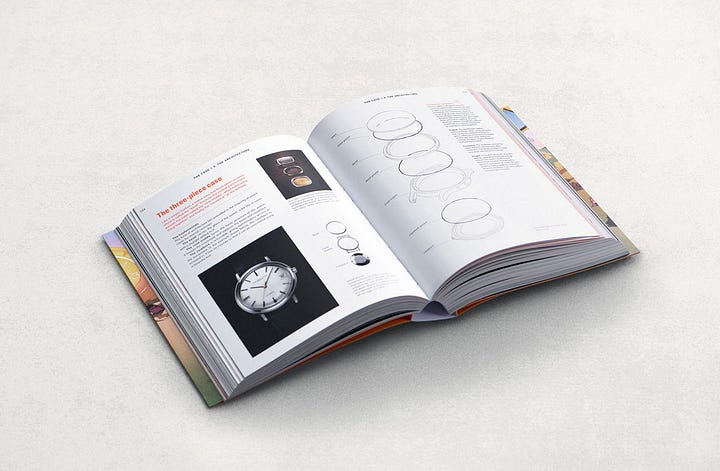

Audemars Piguet released a good book. To mark its 250th anniversary, AP has published The Watch. I asked for a preview and was sent a PDF of all 700 pages, but enjoy it enough that I’ll order a physical copy. It takes you through every part of the watch in some detail: Dial, case, bracelet, movement, and complications. It’s AP-focused, but the info about techniques and components is broadly applicable. For example, some of the content in the “Dial” section is similar to Dr. Helmut Crott’s book of the same name. Tons of images, and the price feels reasonable: On Amazon, I’ve seen from $78 (as I write this) to $95. (Amazon)

How to Actually Develop ‘Good Taste’

Jimmy asks:

“Hey Tony, any advice on acknowledging and being comfortable with what our actual taste is? Determining what watches we actually like versus the ones we think we should like or are an impact of perceived social pressure/influence (the ones we see on Instagram or that give us some kind of credibility)?”

Good question. In some sense, it’s The Question. The core challenge not just of collecting, but of spending money on anything we want after our basic needs like food, shelter, and fast WiFi are met: What do I genuinely enjoy, versus what am I being told that I should want?

For those of us who live in a post-industrial world where we’re spoiled for choice, taste is everything. We’re pelted all day by the modern firehose we call the internet. Social media shapes what we want, whether we admit it or not. Our taste is reflected in the choices we make, what we buy, what we wear. Taste is discussed, debated, even trotted out as an antidote to this thing called “AI.” The highest compliment you can pay a collector is that they have “good taste.”

But what does this even mean?

Good taste isn’t about following rules or rejecting them. It’s about building discernment over time—learning to recognize what moves you, why it moves you, and when you’re being moved for the wrong reasons.

Discussions about taste often leave me wanting more. They’ll default to rigid rules (“no date windows!”) or worn-out idioms (“buy what you love”). But how should we actually consider the collecting world and its many niches, from vintage sports watches to neo-vintage complications to modern independents? Historically, good taste was codified—so-called authorities dictated what it was and wasn’t. A generation ago, that might’ve been some adherence to classics, an appreciation for Patek Philippe World Timers or Breguet pocket watches. Today, those rules have largely disappeared. The aperture has widened to include a broader cross-section of culture.

That’s a good thing. But that also makes it harder to critique ugly watches—a bad thing!

In prepping for this article, I started asking people: What do you think it means to have good taste? Surprisingly, I kept getting one answer: Good taste is individual. Jimmy’s question gets at this intuitively. The question was not “how do I develop good taste?” but how do I understand my own, actual taste?

Let’s start by going back.

I: A Brief History of Time and Status

First, let’s acknowledge that our judgments about watches are not neutral or objective. They’re rooted in culture, class, and identity. We can’t collect in a vacuum. In a recent review, a couple of comments asked if my take was really objective. Of course not!, I said.

Watches, pocket and wrist, are deeply intertwined with industrialization. Back when we lived on farms, “time” was more or less dictated by the sun or tides. Sun rises, rooster crows, at it again.

But when industrialization came along, it became important to be on time, whether you were a train or a factory worker. Time became commodified—“not passed, but spent,” British historian E.P. Thompson wrote.

At first, pocket watches were expensive, the province of factory owners and capitalists. Especially prestigious were new-fangled keyless pocket watches, invented in the 1840s by Jean-Adrien Philippe, who would co-found Patek Philippe. His invention allowed for watches to be wound by the crown, dispensing with the traditional key. These were called “stemwinders,” a term that’d later be used to describe an impressive person or a rousing speech—watches and status, already intertwined.

But mass production came soon enough, particularly in the United States. In 1860, Waltham made about 20,000 pocket watches; by 1890, it was making ~800,000. In 1896, Ingersoll introduced its $1 pocket watch. Suddenly, the average American could afford a pocket watch. That’s how it usually went: from the rich to the rest. The watch was democratized.

“The clock, not the steam engine, is the key machine of the modern industrial age,” American historian Lewis Mumford would write. The watch kept the railroads, and then us, on time. Factory workers punched in and out, selling their labor by the hour. “Time is money” still rings true today. Ask any lawyer at any fancy firm, and they’ll gladly complain about billing time in 10-minute increments.

After the pocket watch, the World Wars popularized wristwatches. Then came the rise of the professional class and the proliferation of mid-century dress watches. Even sports watches, like chronographs or divers, were for the leisurely activities of a new middle class. When the hippies came along, marketers started using the language of individualism to sell stuff (Rolex’s “If you were…” campaign). As advertisers learned to cater to ’60s counterculture, cool became fuel for consumers. Then quartz came along, mechanical became a luxury, and “Swiss Made” its own brand.

While the measurement of time is scientific, our clocks and how we divide that time into hours, minutes, and seconds are a construct that shapes our relationship with time and timekeepers. Once time became something to be owned, so did taste. Watches became not just tools for time, but objects for signaling discernment.

II: A Foundation for Thinking about Taste

There’s this old-school view that taste is some universal, objective truth. Everyone gets that a rose, sunset, or Patek Philippe 1518 is beautiful. I think it goes back to Plato. This can lead to the formulation of strict rules—the Golden Ratio, the Rule of Thirds.

For collectors, it also means an adherence to certain rules. A dress watch must be slim, in precious metal, preferably on a black strap. It’s an analytical approach that can feel like it makes sense, especially for objects grounded in mechanics and engineering. Forums and comments sections feast on arguments about specs, complications, and Spring Drive.

The opposite extreme is the postmodern idea that good taste is subjective, or put another way, “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” But if everything is good taste, then nothing is. I don’t know about you, but I can’t find much beauty in this.

Some thinkers have tried to split the difference:

David Hume said taste is personal, but not arbitrary. He called it a feeling, but one informed by knowledge, experience, and judgment. He imagined a “True Judge,” someone with a trained eye and calm mind who can look at a Patek 1518 and sense its harmony. Kant called this disinterested pleasure: the idea that something is beautiful when you enjoy it without needing to own it, flex it, or justify it.

Others built on this by exploring how class and identity influence taste. George Simmel famously wrote that fashion arose out of two natural human tendencies: (1) wanting to fit in with a group, and (2) wanting to stand out as an individual. Taste isn’t just you, but also the culture you live in. This is especially relevant for an object like watches that have always been wrapped up in signaling and status.

III: How to Develop Your Taste

Hume gives us a starting point for being better collectors without becoming total snobs. He says a True Judge has five traits, all of which sound pretty useful:

Delicacy of Sentiment: Attention to the most subtle details. Focuses on our perception.

Strong Sense: Sound judgment to grasp the overall structure, purpose, and relationship between parts. Intellect.

Practice: Experience. Exposure.

Comparison: To other watches. Context.

Freedom from prejudice: Setting aside personal biases. Impartiality.

But we also must acknowledge the world we live in, where we’re free to collect whatever we want while being constantly bombarded with choices. We want the respect and admiration of others, and fool ourselves into thinking buying things can get us there. But here’s the problem: if that’s how you acquire, it’s just as likely to induce envy as admiration. We also overestimate how much people actually care. When I see a nice pre-Daytona 6238, I imagine myself wearing it. I’ve forgotten whoever’s actually wearing it. This is the paradox of collecting for attention: no one’s watching as closely as you think. Taste is what remains when the audience disappears. It’s earned, not bought.

A few more suggestions for developing good taste that build on the unique history of watches and the work of philosophers smarter than me:

Be independent. Good taste is freedom. From the algorithm, from feeling like we “should” buy something to “check the box” (don’t ever tell me you bought a watch to check the box!) It’s being able to look in the mirror and say: If no one else knew I had this watch, I’d still love this watch. Two examples:

Be unpredictable—look beyond The Kit. If I can look at the first three watches in your box and guess what the next one is, it’s probably not that interesting. Years ago, I talked to Michael Williams of A Continuous Lean, who said he struggled with the person who had “all the grail items: a Porsche 911, a Daytona, a Leica. “Putting it all together, it’s like you saw the ads and just bought the whole kit.” Since then, I’ve thought of this as The Kit. Don’t buy The Kit. It’s the collecting version of those starter pack memes.

Don’t buy just the expensive sh*t. Similarly, it’s not fun just to buy the most expensive thing. I always think back to this single-owner sale. What do a Philippe Dufour Sonnerie, Marlon Brando’s GMT-Master, and this thing have in common, except that they’re all very expensive? They don’t seem to illustrate any level of curation or thought, beyond a desire to build the “most expensive” or “most important” collection, always a fool’s errand. Expensive stuff can be cool, but I also want to see the weird, original stuff that no one understands. That’s interesting.

Look beyond the icons. When you start collecting, there’s a tendency to focus on the “icons,” or maybe the “everyday” watches. It’s a good place to start. But to develop taste, eventually you’ve gotta try the weird stuff. If your goal is finding your taste, a one-size-fits-all approach only goes so far. Enjoy finding the obscure watches that no one else does, or having the small gold dress watches (or massive dive watch) that you only break out for rare occasions.

Focus on the details. To expand on Hume’s criteria: this can be easier than it sounds. I read this fun book about art last year, where the author got advice from an art critic on how to appreciate art. The advice, to paraphrase: Stare at a painting, undistracted, for five minutes, and make five observations about it. These can be as simple as, the grass is green, I don’t like the shade of green because it reminds me of what my cat coughs up on the carpet. Notice the details others miss, or simply don’t take the time to appreciate. I’ve seen Mark Cho pick up a watch and first study case ergonomics for a few long minutes; I’ve seen Erik from Hairspring start by louping a movement’s finishing. Different things matter to both, and that’s what makes it fun.

Think of collecting as a language. Menswear guy Derek Guy once wrote “dress is like a language.” Kind of like how a good sentence is more than just following grammatical rules, it’s about considering how each part comes together to create meaning. Language is a way of expressing yourself, and collecting can be, too. Questions of taste are more easily answered if you think of collecting as a method of communication. Look at the IG of Watch Brothers London or Lydia Winters, and you immediately see how they tell stories about taste and what’s important to them.

Find a niche. A subscriber once told me he was given the following advice from the chairman of an auction house’s watch department: Start with a niche, vintage Patek Philippe if you can, then take what you learn there and apply it to other categories. Most of us probably aren’t starting with Patek, but especially in the beginning, you’ll probably learn more by going deep in one category than going wide in many. Expand later. In today’s world, where there are no rules, it helps to go deep in one category and formulate your own framework for collecting and build from there.

Strive for individual coherence. Your collection should have an individual coherence in terms of how it fits together and reflects something about you. An Omega Ploprof may not be coherent for me, but it works on Gianni Agnelli. The watches you collect should, first, be an accurate representation of you. If someone saw them in a watch box, they might recognize them as yours. Then, how are these watches in dialogue with each other? Is the sum greater than its parts?

Rely on people and stories. Every brand wants a direct connection with you, sometimes they’re even opening their own boutiques. But there’s still value in finding people—retailers, media, collectors—who you trust and learn from. There’s value in going into a multi-brand store with a real POV on which brands they carry (or don’t), and why. The same goes for writers and creators. Find people who have a coherent perspective. Look for vintage sports Rolex from Dr. John Field or Langepedia for you know what.

Skin in the game. At some point, you have to buy stuff. If you want to know if the Black Bay Pro really is too thick for you (it is for me), you have to live with it. Wind it every day. Luckily, the secondary market has gotten easier and safer to navigate. Go slowly, collect information from every experience, and let it guide your next acquisition. Hardly a week goes by that I don’t have a transaction on eBay. Collecting’s not something you finish, it’s something you refine. Ultimately, you’ve gotta have skin in the game.

IV: Knowledge

Watches let us measure time, but collecting lets us appreciate it. Mass-produced watches put time on everyone’s wrist, but this also turned time into something to control, optimize, and quantify. The real practice of collecting is slowing down: noticing what moves you when no one’s around.

The old rules for collecting are mostly gone. Influence flows from the bottom up just as easily as top down. Brand leaders make TikToks with dealers, who might get inspiration from music or art. This is good—we’re not constricted by old rules about what we should buy. Having good taste isn’t just about having money, power, or access. It starts and ends with knowledge.

It’s what separates thoughtless acquisition from a collection with meaning. I’ll leave you with this, from wine critic Roger Scruton’s I Drink Therefore I Am:

“The most important thing to remember when exploring Burgundy is that the world is full of people who are both very rich and very stupid, who can be relied upon to spend virtually unlimited sums of money on products about which they know nothing except that other people as rich and stupid as themselves are spending unlimited sums of money on them. These people are extremely useful to the rest of us, since they put a premium on knowledge. Thus you can know immediately that you won’t be able to afford Le Montrachet, but that it might be worth visiting the place next door.” h/t A Suitable Habitat

It’s the same in watches. And if all else fails, remember:

This one got a bit philosophical—I hope it was useful. Let me know what you thought:

Further reading:

The Conquest of Cool, Thomas Frank

Of The Standard of Taste, David Hume

How to Develop Good Taste, Part I, Die Workwear (Part II)

Time Consciousness and Discipline in the Industrial Revolution, Watches by SJX

The Art of Spending Money, Morgan Housel

What is Good Taste in Watches, Screwdown Crown

I tried to read some Kant but find him unreadable; I’m pretty sure I got by on Spark Notes in college, too.

Tony when I submitted my question regarding taste, I did not expect an entire post let alone an essay analyzing the nuance and the building block of each of our own tastes. Bravo my friend.

I read through this several time and listened to the audio (I think I speak for many when I say keep that up too) to digest all the thought you put into this. I realized that a lot of this development really does come naturally over time as well as with experience. You even mentioned that I naturally did not ask about "how to develop taste" but "how do I understand and develop my own taste." We may fight what we truly like in lieu of what we think will get us the perception we think we desire, but I like the line about "what makes you happy when no one else is around" and "would I like this watch even if no one knew I had it?" I think we can all let those be our north stars. To many people these days seem to gravitate towards "the kit" and that really is a fools errand and something I have been cautious to avoid unless a piece of it truly resonates with me. Surprign people and yourself seems way more fun! I don't think any of my watch friends expected me to come back from Japan with a Kurono Vermillion Salon edition over a Grand Seiko. Especially after how much I obsessed over a myriad of GS.

Last thing I'll say is slowing down and taking things in is something I am trying very hard to be mindful about in my daily life so I am very glad that was a relating point here. It's tough , but it makes life a little more interesting and allows you to take it all in.

P.S. I appreciated just how when I was thinking that I'd like to know what further reading to do including the comparisons to the fashion industry and the human condition, BAM you put it right there for us. I'll be brushing up on some of this.

Enjoyed the very well written article. As an old philosophy major I appreciate the inclusion of Kant and Hume into this newsletter 🤣, but having been around watches for most of my life, I’ve long since figured out what I like and don’t like. I don’t dwell upon whether my collection is in “good taste” by some preset third party standards because they all reflect my personal preferences and work for me. BTW, Kant didn’t make sense for me either. Painful reading IIRC. Something lost in translation methinks…