Good morning from New York, where I’m filming a “Masterclass” for Teddy Baldassarre’s updated website. In today’s newsletter: My complicated feelings on microbrands; vintage and modern (and the myth of ‘vintage’); GMTs under $30k, and more from last month’s Q&A.

🎧 I tried something new: This week’s Q&A is also available as an audio issue. It feels like a format that naturally lends itself to audio. Listen above or find it on Spotify / Apple / RSS. Let me know if you like the format, and I’ll think about using it for future newsletters.

📚 I’ve mentioned before that Rebecca Struthers’ Hand of Time is one of my favorite books about watchmaking. She recently published About Time, a children’s book on the history and science of time (ages 7–11). Dr. Struthers’ co-author is a physics teacher, and they’ve managed to make a complicated subject approachable and fun. Great for kids, and while, like me, you might be outside the recommended age range for this book, you’re certainly not above it. Also great to keep in mind as the holidays approach. Amazon | From the publisher.

ICYMI

Q: What are your thoughts on every microbrand coming onto the market? What space do these microbrands fill, and do you think these brands will survive such a harsh and competitive market? –Ron

A bit of a leading question, but it accurately captures my complicated feelings about many small or microbrands (not unlike my feelings about Watches & Wonders). I like many of their watches and have bought more than my share.

That said, there are also a lot, perhaps too many, and I struggle with the fact that they’re often bringing together existing suppliers and components in different ways. No doubt, many of these microbrands do this while offering interesting designs or a unique perspective (Brew, Studio Underd0g). Some have even used this as a stepping stone to developing more interesting or complicated watches (Ming, Furlan Marri). Hell, Nomos started off using Peseux 7001s. The line between microbrand and independent is also increasingly blurred.

Still, I appreciate watches for their enduring quality, and wonder if some of these microbrands will live up to that standard. I wonder how many brands at the typical microbrand-focused show will be around for the next one. Watches used to feel like this escape from the fast consumerism we see in so many other categories, but no longer. But perhaps this also gives established brands too much credit??

I’ve bought a handful of these watches. Honestly, the only one that’s really stuck is an Oak & Oscar, and that’s largely because I feel a personal connection to O&O as a local Chicago brand I’ve followed for most of its existence.

Which gets to another reason why there are so many microbrands: We develop these personal connections for all kinds of different and perfectly valid reasons. Global supply chains and the internet make it a pretty viable business, and perhaps that’s just fine.

Q: I’m trying to add a GMT/dual time/world time to the collection, but struggling to find the right piece. Don’t want Rolex, but want something wearable that I can actually travel with and feel safe, new or vintage is fine, just not the same old GMT-Master. $30k budget. –Marc

I like the Parmigiani Tonda PF GMT Rattrapante at pre-owned prices right now (~$20k), a really subtle and different take on the GMT that’s easy to use. To me, the platonic ideal of a “travel time” doesn’t need to be taken off and set as you’re taxing on the runway. The 90s Royal Oak Dual Times (the original ref. 25730ST) should also slip in right under the budget—midsize proportions (36x8mm!) and practical complication, there’s nothing like it in the modern Audemars Piguet catalog. AP produced the Dual Time throughout the 90s, starting with the old-school tapisserie pattern but eventually transitioning to grand tapisserie.

It later added a larger 39mm, though I’m not sure if a Royal Oak is “safe,” depending on what you meant by that. The modern Vacheron Constantin Overseas Dual Time is also cool. The Lange 1 Time Zone, first introduced in 2005 and updated in 2020, is a bit larger, but an awesome watch on the secondary.

I’ll also add, and to further complicate my previous answer: If you just want to experiment, some microbrands do cool GMTs for cheap since flyer GMT movements have become so accessible: Lorier, Lorca, and Nodus come to mind.

And of course, we have to mention the Nomos Club Sport World Timer again ($5k), now with three new colors:

PRESENTED BY THE COCONUT GROVE WATCH & JEWELRY SHOW

The inaugural Coconut Grove Jewelry & Watch Show, taking place November 14-16, 2025, at The Hangar at Regatta Harbor, will feature a global roster of world renowned antique, vintage and estate dealers. Join fellow watch enthusiasts and uncover exceptional and rare vintage and estate watches that cannot be sourced anywhere else. This three-day shopping event is your invitation to indulge!

For complimentary tickets, register today and use promo code UNPOLISHED:

Q: I have more of a philosophical thought: We hear so much about the soul and beauty of vintage and the sterility of modern timepieces. Your most recent interview [with Ben Dunn] is a good example of this. But what is now vintage used to be modern. And what is now modern will someday be vintage. What are your thoughts about the progression of modern watches to vintage? –Eric

Q: What is your view on people only talking about mainly 60s–70s watches when it comes to vintage? Should someone who, for instance, collects TAG Heuers from the early 2000s be accepted as a vintage collector in the same way as someone who has Heuers from the 60s? –Patrick

It’s interesting to see how watches from the 1980s–2000s are now treated more like “true” vintage watches, with an emphasis on condition, originality, and other attributes important to collectors. This also means how we think about servicing them (or not), as what becomes more important isn’t the watch’s performance, but its condition and originality.

There’s this commonly parroted myth that vintage comes from the French for 20 (vingt). It’s not true, but provides a useful rule of thumb, even if I think the definition is more fluid and varies by brand.1

For example, Rolex is the easiest as its modern era sees the advent of five-digit references that introduce sapphire crystals, glossy dials, white gold surrounds, and Luminova compounds. Meanwhile, Patek Philippe transitioned from engraved enamel to printed dials. That said, many of these watches, like the Patek 3940 or 3970, might be classics even if they’re not fully vintage yet.

More broadly, the 80s and 90s were defined by the widespread adoption of computers, CAD, and CNC, and watches produced using these tools can just feel different than what came before. These modern manufacturing techniques allow precision, which means tighter tolerances, more complications, and so on. Of course, future tech could do the same for future watches.

In the process of modern turning into vintage, there’s an important “filtering” process as collectors, enthusiasts, and archivists decide what’s important. Anyone with an eye towards documenting, preserving, and defining that history can be a “collector.”

It seems to take about 20 years (a generation) for this process to happen, and it’s no coincidence that there’s been a broader return to 1990s/early 2000s culture the past few years. It’s fascinating to watch it happen in real time as we have been with the neo-vintage era in watches. Some watches like the Breguet ref. 3350 tourbillon are deemed classics while many others wallow away in relative obscurity.

Q: What really is a “Frankenstein” watch? Levels, types, and can any still be worthy of love? I ask because although swapping out a basic dial for one of a rarer model is obviously egregious, the rest, short of swapping out whole movements seems less obvious. In any proper service, parts will routinely need replacing, and hands are routinely replaced. So what is “all original”? Is there a normal amount of replacements where a watch is not Frankenstein or at least still a loveable one? –Paul

A question that will be debated as long as we’re collecting watches or similar objects. In general, dial, case, and movement being born together is the most important inquiry, but even then, it gets tricky.

In an article on restoration, I spoke with Eric Ku and Beau Goorey of LA Watch Works. Beau, LAWW’s watchmaker, said he doesn’t get hung up on replacing what he called “general wear items” like crowns or crystals, “as long as they’re genuine Rolex parts.” That’s a good guiding principle, though it gets tricky in the details.

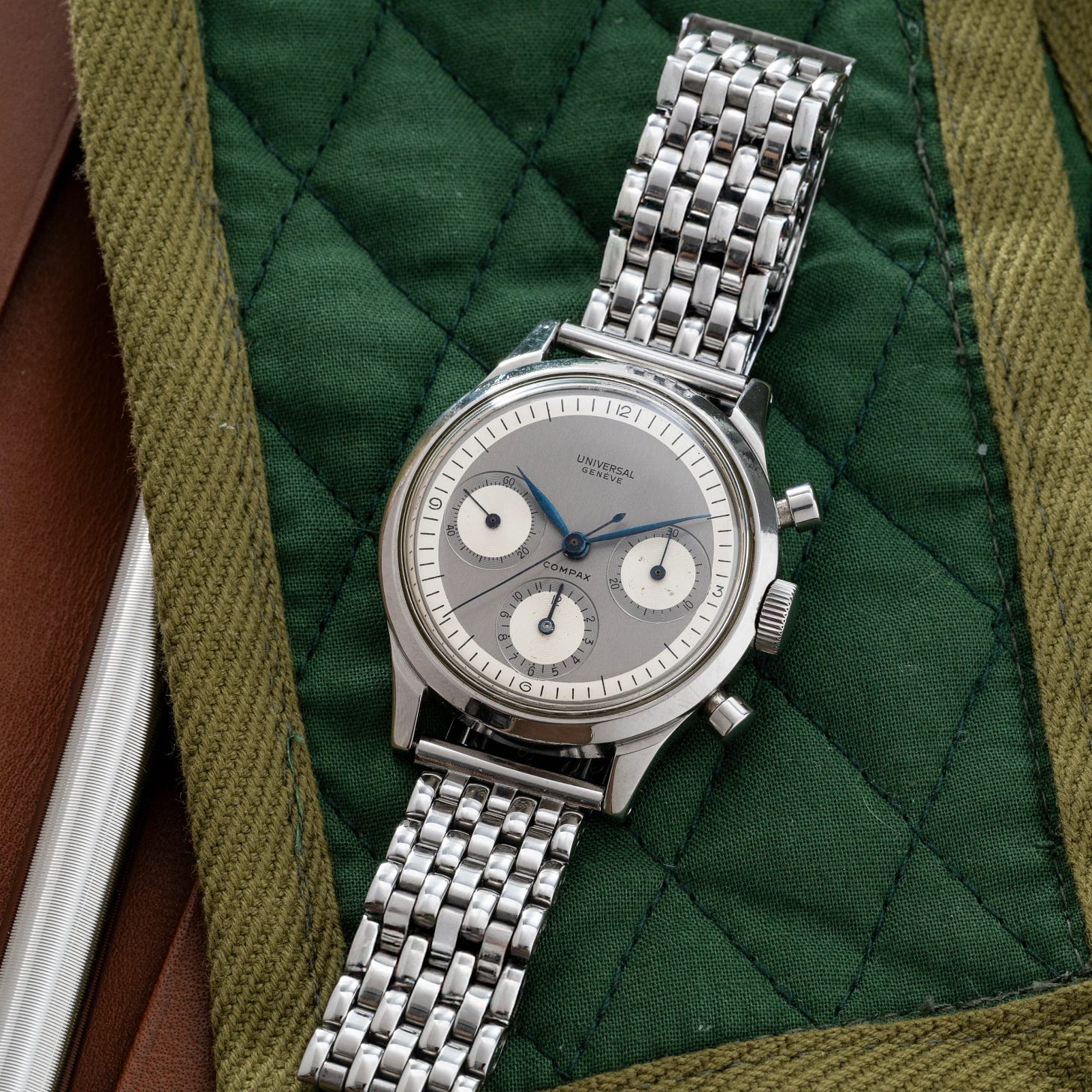

Omega and Universal Geneve collectors love to see the engraved logo on an original crystal. If you’re looking at First Series Rolex Daytona, you better know if it has the original millerighe pushers.

Originality falls on a spectrum that looks something like this:

Original/factory. A watch as it originally left the factory.

Period correct. Non-original parts that are generally accepted as correct given a watch’s age.

OEM-authentic parts. Has different or service parts that come from the original manufacturer, but that would not have been seen on that particular watch as it left the factory.

Non-authentic parts. Not made by the original manufacturer.

Most of us would probably draw the line for “Frankenwatch” somewhere in #3, but where exactly is personal. For example:

I recently wrote about those rare Universal Geneve grey prototype dials, which are generally believed to be loose dials placed in cases. Some of you thought it looked cool, others screamed Frankenwatch.

Earlier this year, we covered a Rolex Daytona 6240 with a white Paul Newman dial from Rolex CPO. It’s generally believe that dial isn’t period correct for this reference. It also had later pushers, crown, and bezel, even if they were all authentic service Rolex parts.

Once a watch gets too many components that are either service parts or not correct, it can start to look like Frankenstein’s monster. Instead of just calling a something a Frankenwatch though, it is important to understand what components fall where on the spectrum, so you can decide if that matters to you.

I generally believe that every watch has a price, but if it’s not put together correctly, a watch’s price may not be greater than the sum of its parts.

Q: I’d love to know a bit more from behind the scenes of Unpolished: (1) Each newsletter, do you have a dedicated time to write everyday? Photography wise, how is the balance between getting the “ideal” shot IRL when the collector or brand is also present, in the sense of: should we chat or should I take pics? I imagine that scenario being quite tricky at events and releases in particular. –Paulo

Totally self-indulgent, but here we go. I work from home, and do my best writing first thing in the morning after walking the dog. I’ll often change locations in the afternoon, I like being in public where I feel like people are judging me if something’s on my screen that seems unproductive. The afternoon is often spent on more administrative tasks. I’d bet it takes three days to put together 2 newsletters/week. The rest of the week I work on bigger projects for the future, or for other publications and clients.

(2) has changed a bit. Nowadays, Instagram emphasizes video so much, getting the best photo is less important than getting a short clip that can be used for a video when you’re in a pinch. So I emphasize trying to talk to people more now and make an actual connection. The newsletter also lends itself to this: I can get better newsletter content from a conversation if I ask interesting questions that no one else is, and sometimes I even like the “unpolished” feel of a mediocre photo in the newsletter.

A newsletter is somewhere between a long email to friends and a short essay, and sometimes images can fit that brief, too. That said, sometimes I do care about the images, like last week’s visit to Glashütte.

CLOSING THOUGHT

👉 Dr. Helmut Crott was awarded the Gaïa Prize, an annual award honoring contributions in horology by the International Museum of Horology. From his acceptance:

“My wish is that the watch industry learns to resist certain temptations inherent to the luxury sector—temptations that, in the pursuit of higher sales, blur the distinction between consumer products and exceptional objects.”

Thanks for reading. Get in touch:

tony[at]unpolishedwatches.com

Tap the heart or leave a comment:

Vintage shares a Latin root with the French word vendage, meaning “grape harvest.” The meaning of vintage evolved from referring to the year’s wine harvest to its broader sense of something classic, of high quality, or from an earlier period. It has nothing to do with 20—it’s fine to make the argument that vintage is anything 20+ years old, but don’t use French/Latin etymology to make your point!